Bernice Robinson was born in Long Branch 100 years ago and still lives in the same home her dad built. Robinson family photos.

Easy going centenarian Bernice Robinson has lived in Long Branch her entire life and remembers when the area was farm country with dirt roads.

Robinson, who turned 100 last March 25, was presented with a bouquet of flowers by members of the Long Branch Neighbourhood Association to mark the special day.

She says her secret to a long life is to keep mentally active, live a clean lifestyle and remain busy with church activities.

Bernice as a young girl when she and her friends swam in Lake Ontario three times a day and played in the fields. Robinson family photos.

Robinson is mentally alert and has a great memory, so much so she remembers when the trolleys (now streetcars) that ran along Lake Shore Blvd. W., cost about 10-cents and had pot-belly stoves that were continually filled with coal to keep passengers warm.

“There was a lot of heat but many times we were cold,” she recalls. “On cold days the conductor had to keep filling it with coal.”

Back then the trolleys frequently came off the tracks, the streets weren’t numbered as they are today and most people knew each other.

“There were four movie theatres and it was a country village,” the active church-goer remembered. “The theatres used to give us bowls or plates every time we went to a movie and after time you would have a whole set.”

The people walked everywhere since ‘you were considered rich if you had a car.’

“We went swimming three times a day in the lake and took part in church activities and that would be our main entertainment.”

Back then Marie Curtis Park area was busy with wartime activities with the Small Arms building and a shooting range for soldiers to practice.

The Lake Shore strip was a collection of small stores with fields, dirt roads and empty spaces between the businesses.

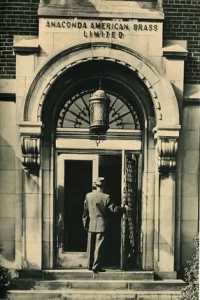

The area was alive and most people held jobs working at Goodyear Tire, Campbell Soup, Anaconda American Brass, W. & A. Gilbey’s Distillery, Reg N. Boxer; later called Canadian Wallpaper Manufacturing Limited, Ritchie and Ramsey Paper Mills, DuPont’s Fabrikoid, George Williams Shoes and Continental Can.

“Those companies opened up the area at that time,” Robinson explains. “It was a good time for the community.”

Robinson said the boom took a dive after WW11 ended.

She recalls the Great Depression in the 1930s when as many as 2,168 Etobicoke men were unemployed and receiving relief benefits in cash or in vouchers that could be used to buy food and other necessities.

“After the war things picked up a bit but got worst,” she says. “There was little money and no jobs.”

The men in exchange were expected to work on road maintenance or other types of unskilled public work. Rotating strikes and public protests were common.

Robinson said the community has drastically changed for the worst since then.

“Everywhere you go now is tall condos where people do not know each other,” she complains. “People today have no history or don’t know their history.”

Robinson still lives in the same Twenty Seventh Street home that her dad built and was forced to change church after St. Paul United Church was sold.